The desire to “learn from the past” and “not forget” often becomes an organizing principle for moving forward from calamity, with recovery as the process that connects the past and the future. In the wake of the 2011 earthquake and tsunami, the Japanese phrase wasurenai (never forget) has been widely invoked. Never forgetting takes on a dual purpose: it memorializes and affirms community identity, but also acts as a kind of clarion call for doing things differently to prevent future disasters.

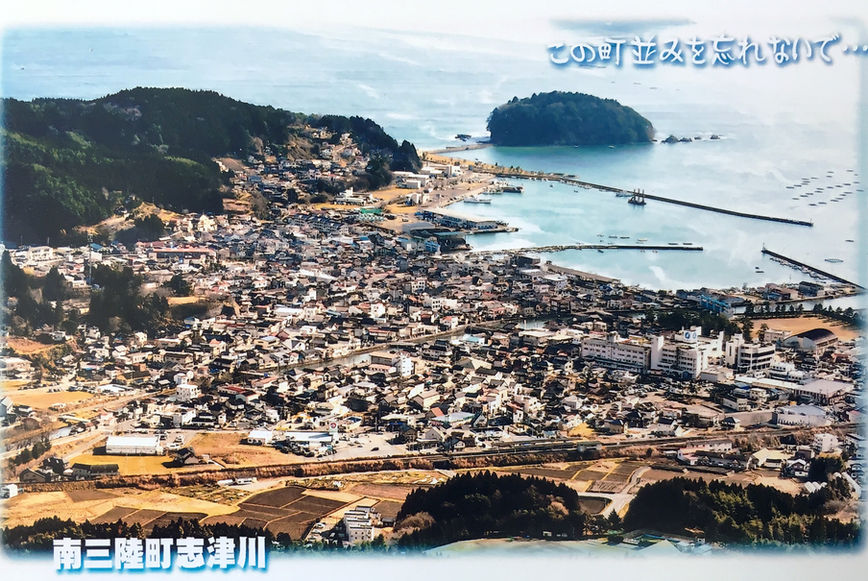

But what to preserve, what to reconstruct, and what to build wholly anew in these coastal towns continue to be contested and difficult questions with disputed answers. The decisions to preserve the ruined Ōkawa elementary school in Ishinomaki or the skeleton of the Disaster Management Center in Minami-Sanriku as memorials to the tsunami, for example, have been wrought with controversy given the traumatic events that took place there. Meanwhile, the creation of larger sea walls and levees on the coast has been met by strong opposition due to the impact these structures have on the perception of and connection to the sea and the the larger environment.

Remembrance of the past serves as a motivating force for the future, but a contested one in terms of the exact shape its takes. Indeed, for every mention of wasurenai one comes across, the saying ganbarō is not far behind. While ganbarō has no exact equivalent in English, it communicates a kind of encouraging and aspirational striving, something akin to phrases like “fight!” or “do your best!” But like much of rural Japan, many towns along the Sanriku coast have experienced economic downturn and depopulation for decades, and the events of 2011 only exacerbated those trends. In that light, ganbarō was already a valuable resource. Given the now-accelerated changes in population size, demographics, and economic prosperity, fundamental questions about cultural continuity and aspiration come to the fore as reconstruction progresses, and in very practical terms.

- Click on the images for a more detailed description of each -

Following the clean-up phase post-tsunami, the memorial and mitigative roles of remembrance have expanded from the highly local constituencies of the coastal communities to widely distributed and global ones. While watching television in my motel room in Ishinomaki, I was struck by a program following a delegation of disaster planners from five different countries touring iconic cases of tsunami damage in the area, including local elementary schools. Although a global network of governmental groups and NGOs have been involved immediately after disaster struck in 2011, continuing to draw outside interest and international connections has become a characteristic of the region's recovery efforts.

This became even clearer to me while visiting the Ishinomaki Community & Information Center the next day, which is devoted to the 2011 earthquake and tsunami. I met with the center's director, Richard Halberstadt, a British expat but also a local community member in his own right, having lived in Ishinomaki for over twenty years. Richard and I sat down and talked in the center's Exchange Corner, designed, he said, “for residents to come and talk about what kind of Ishinomaki they want in the future.” Despite this sense of local community focus, Richard tells me that the center primarily serves out-of-town visitors, with about 85 percent of its visitors from outside Ishinomaki and 15 percent from within. Connecting outward and globally appears to be built into the city's own aspirations for the center, as the decision to appoint a foreigner as the director would seem to attest.

Later, I come across a 2016 article about Ishinomaki in which Richard is featured. The author mentions how:

“while more international tourists are visiting Japan than ever before, few of them choose the Tōhoku region as a

destination, much to the dismay of the local tourism and hospitality industries . . . . The city is no longer in shambles.

The rubble is gone. The demand for volunteers has greatly diminished. ‘But we still need people’s help, even if it’s

just in the form of tourists coming to buy our products and support our economy,’ says Halberstadt. ‘I tell everyone

who comes through here, “Please don’t forget about us. Come back and see us again.” If they go home with

memories of Ishinomaki and a better awareness of disaster preparedness, then I feel we’ve done our job.’” ^

Disaster planners from five countries visiting the region and observing tsunami damage. The caption mentions the delegation's visit to the Arahama Elementary School in Sendai, and a visit the Okawa Elementary School in Ishinomaki, in the coming days.

350 students at the Arahama Elementary School survived the tsunami by escaping to the roof. The building has been preserved, as is now advertised on Sendai's official tourism website. Eighty-four students and teachers died at Okawa Elementary School after a failed evacuation. Only in 2016 did the town come to the decision to preserve its ruins for memorial purposes.

Indeed, Richard tells me that the main work of his position is wasurenai, and that makes a lot of sense. In some ways, educating about the disaster and memorializing it (wasurenai ), has become a ganbarō force in the coast's economic recovery in its own right. By globalizing a combination of hope, practical disaster prevention, and new forms of so-called disaster tourism all at once, the tsunami communities are creating novel, synthetic aesthetics of regrowth.

Moai, the adopted symbol of the town of Minami-Sanriku, is a case in point. In 1960 a powerful earthquake off the coast of Chile generated a tsunami that crossed 17,100 kilometers (10,600 miles) of the Pacific Ocean and caused substantial damage as well as casualties in Minami-Sanriku, motivating the construction of a five-meter protective sea wall in that coastal town. In 1990, Chile sent replicas of Easter Island figures (moai, in the native Rapa Nui language) as a gesture of solidarity and memorialization of the 1960 disaster, only to have them knocked down by the 2011 tsunami.

New moai —quarried from rock in Easter island and carved by a Rapa Nui artisan—have now arrived since 2011. They are not only the town's “symbol of hope for the future,” but have also become a mascot whose visage and narrative forms a large part of the town's recovery tourism economy. Agence France-Presse reported in 2012 that local students were, “developing ‘Moai-yaki’ buns—sweets with custard or bean paste inside—which they hope to be able to send to market. School teacher Yasunori Mogi, 29, said projects like these could prove invaluable experience for youngsters in a town with few job opportunities. ‘Unless these children can find their places in this town, we won't be able to rebuild the community in any real sense,’ he said.” ^

- Click on the images for a more detailed description of each -

Just as the Sakuteiki (see Borrowed Landscapes) makes clear, the setting of stones is the foundation of garden construction. In this case, the moai stones are tsunami stones, but of a very different kind than those left in generations past. Rather than marking higher ground, they help cultivate a sense of the whole Earth as a shared locality where narratives can be fashioned across space, time, and divergent cultural contexts into a remarkable mash-up of glocal character. The planetary scale of physical phenomena like earthquakes, tsunamis, and global warming are interlaced with the ever more global nature of communication and economy, and thus a sense of shared experience.

For example, in a booklet from the village of Ogatsu in Ishinomaki, titled “Stories of Great East Japan Earthquake—Psychological Care for 3.11 Victims and Education Program for Disaster,” the author's first gesture is to “express appreciation to people who support us victims of 3.11 earthquake, especially to the families of 9.11 . . . ” Thus, events as distinct as the 2001 terrorist attacks in New York and the 2011 tsunami in coastal Japan are connected through a sense of solidarity based on shared catastrophic loss, despite the fact that they are born of entirely different circumstances.

A new roadway connecting here to there and now to then in Minami-Sanriku, Japan.

These forms of disparate solidarity provide an interesting counterpoint to struggles within Japan to meaningfully gather, discuss, and negotiate different viewpoints both within and across residents and governments (municipal, prefectural, and national). Like so many other recovery and rebuilding efforts, the reconstruction of the Sanriku coast has revealed the many challenges of collective governance, even within a national culture considered a comparatively homogeneous and consensus-driven.^ While some of the challenges are specific to the cultural and historical milieu of Japan, they are arguably also generalizable to the issues of scale, risk, and autonomy that communities across the planet are confronting more and more in the face of the varied disasters that are all consequences of a planetary global warming (armed conflict, mass migration, extreme weather, decreased food security...). The possibility aesthetics of the Anthropocene—who is aware of what, shares affinities, and collaborates with whom—remains an open and pressing question. The gardening is not wholly top down nor bottom up; it is diverse and emergent across networks of connectivity that are as surprising as they are meaningful. All sorts of strange things bloom and the landscapes of terraforma are anything but just native.